The

Library History Buff

Promoting the appreciation, enjoyment, and preservation of library history

The

Catalogue Cards of the Harvard College Library

I have an interest in catalog cards and card catalog

cabinets that is reflected in both the

Library History Buff Blog and the Library

History Buff website. Allen Veaner, the former

Director of Libraries at the University of California at Santa Barbara, became

aware of my interest in library history and contacted me to see if I would be

interested in a collection of "catalogue" cards that he had salvaged from his time

as a cataloguer at the Widener Library of Harvard University. I, of course, said yes. The collection

was of particular interest to me because of the role that Harvard played in the

early adoption of the card catalog by libraries in the United States and by its

use of a 2

inch by 3 inch catalog card instead of what became the universal standard 7.5 x

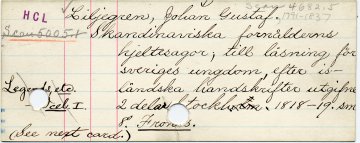

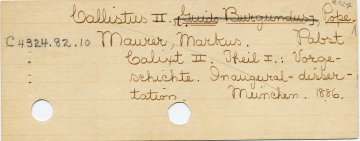

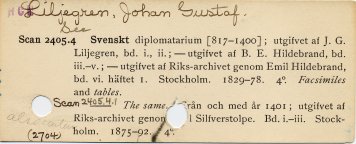

12.5 cm catalog card. Allen's collection consisted of five of the 2 x 3 inch

cards, 42 standard size cards, and three order cards. Below is an essay about

the collection which he was kind enough to provide with the collection. I have included

scans of some of the cards. Click

here for a historical overview of the card

catalog. Click here

for examples and uses of card catalog cabinets. Click

here for

examples and uses of old catalog cards. For more information on early library

catalogs in Boston libraries read: Mitchell, Barbara A. "Boston Library

Catalogues, 1850-1875 Female Labor and Technological Change," in Augst and

Carpenter, eds. Institutions of Reading: The Social Life of Libraries in the

United States (University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), pp. 119-147.

In the Days of Card Catalogues: A Brief Portrait

by Allen B. Veaner

June, 2009

Modern librarians are so accustomed to online systems that most recent

professionals have little or no experience with card catalogs. Here I relate a

few anecdotes about file management in the card era. I hope they will illustrate

the distance we have traveled. The scope of my essay is confined solely to my

experience in Widener library, Harvard University. For two years, 1957-59, I was

a junior cataloguer at Widener, responsible only for descriptive cataloguing;

others—much more senior staff—took care of subject cataloguing and

classification. In my limited capacity one of my duties was troubleshooting

problem entries and resolving inconsistencies in the bibliographic record. Very

often I worked with some quite old catalogue cards, some of which predated

universal acceptance of Melvil Dewey’s 75 mm x 125 mm format.

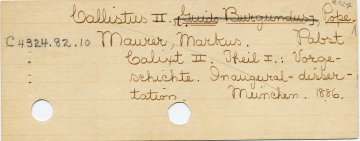

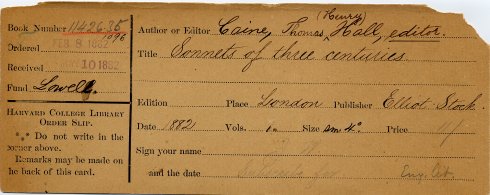

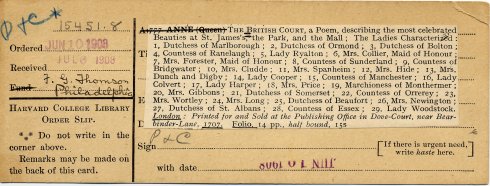

This brief account of my experiences accompanies actual specimens of old,

original catalogue records from Widener Library’s Official Catalogue. When old

records of non-standard size or format were replaced with modern, standard size

records, it was customary to discard the superseded records. However, I

sometimes retained these old records as historical curiosities and now (June,

2009) I am giving them to Larry Nix, well-known library history buff.

Incidentally, fifty years ago Harvard maintained the traditional spelling of

catalogue with the "ue" from the British spelling. I am maintaining that

tradition in this account.

There were two major card catalogues in Widener Library: a Public Catalogue (PC)

on the library’s main floor (the second floor) and an Official Catalogue (OC) on

the first floor where the Catalogue Department’s offices and work areas were

located. As a union catalogue, the OC theoretically contained a main entry for

every title held by the University’s library system, which at that time

comprised nearly a hundred units among Harvard’s branch libraries within the

Faculty of Arts & Sciences, and within the various professional schools (law,

medicine, and others). Libraries outside the administrative jurisdiction of the

Harvard College Library (HCL) did their own cataloging and were responsible for

sending a main entry card to the OC so there could be one place to search for

all holdings of all Harvard libraries.

Changes made in the OC would sometimes require extensive changes to the PC. The

PC held main, title, subject, and sometimes other secondary entries, for

holdings under the jurisdiction of HCL, but not for the libraries of the

professional schools or certain specialized academic units. Holdings of the

entire University Library system were reflected only in the OC, and only by

their main entries. When I replaced an antique OC record of an item also

recorded in the PC, it was necessary to prepare new card sets for the PC to

cover revised title, subject, series, and other entries. Very rarely, a problem

required reclassification. Only the head or assistant head of the Catalogue

Department made the reclassification decision.

Many times it was essential to examine the work itself. Typically, a campus

messenger service took care of bringing distant items to Widener Library so that

I could have the book in hand to prepare a revised entry.

Not all cataloguing was original. Catalogue entries were accepted from several

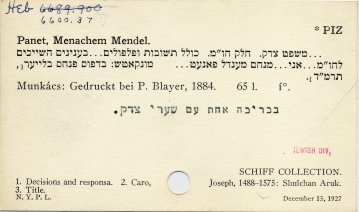

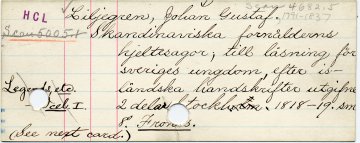

sources and often modified to suit local need. Among the surviving antiques are

handwritten cards about 1 & 7/8” high and 4 & 15/16” long. Some cards of this

same size bear entries locally printed at Harvard’s Printing Office; locally

printed cards are identifiable by the initials HCL, (“HCL” is also rubber

stamped on some entries for locational assistance.) Locally printed cards bear

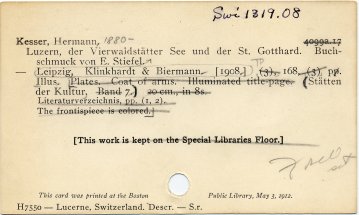

numbers similar in style to those on printed LC cards: the last two digits of a

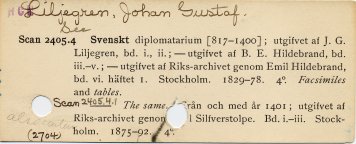

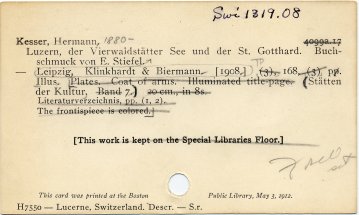

year followed by a sequence number. Besides cards printed at Harvard, HCL

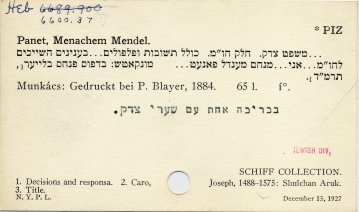

accepted cards from other sources:

Boston Public Library. (Some BPL entries provide the exact date of printing.)

New York Public Library, Schiff Collection (Hebraica)

Library of Congress. LC cards were liberally annotated or altered, and very

often a “proof” LC card printed on thin, cheap paper found its way into the OC.

Entries cut from vendor catalogues and pasted onto card stock.

In Widener Library, and in other units administered as part of HCL, Harvard used

its own classification system until the switchover to LC. Harvard’s alphanumeric

classification system was heavily mnemonic, typically starting with an obvious

abbreviation for a major category, e.g., Ger = German history and culture, LSoc

= journals of learned societies. On the cards, all call numbers were formatted

horizontally, never stacked. This was intended as a space saving device with the

goal of cutting down on the growth rate of the catalogue and thus putting off

the need to buy additional expensive cabinetry.

OC entries indicated tracings on the back for generating additional subject and

title entries intended for the PC. An asterisk preceding a subject heading

informed the typist that an additional set of cards would be needed for a

subject entry. Prior to the adoption of offset printing late in the 1950s, all

card sets were individually typed and proofed. In the 1960s the Widener

Library’s Photographic Department took over all card reproduction, employing the

services of the then modern, high speed Xerox Copyflo printer. (The Copyflo

system for card reproduction is fully described in my article, “Library Card

Reproduction by Xerox Copyflo,” in Library Resources & Technical Services,

8(3):279-284 Summer 1964.)

The library generated series entries only on a selective basis. If no series

entry was to be provided, a main entry card that bore series information was

marked on the back with a tracing: srnk = series record not kept.

In numerous cases, especially with handwritten cards, a call number was added in

pencil and in a different hand. This suggests that earlier in the library’s

history—before the Widener building was constructed—books might have been

shelved by size or were arranged in fixed locations.

Sometimes the only change to a record was the substitution of a printed for a

handwritten card. In such instances, the legend “Substituted card” was

handwritten on the new card.

If an earlier entry was so hopelessly mixed up or new information suggested a

complete reorganization of the bibliographic record was desirable or, for

whatever reason, existing cards could not be salvaged, a new entry was required.

In such cases I would prepare a new, handwritten entry citing other authorities

and catalogues, such as BM for British Museum, BN for Bibliothèque Nationale,

etc., plus arguments of my own in support of an entire reorganization of the

bibliographic record. One such entry (for Gubernatis, LC 7-39363) is included

with the materials I am forwarding to Larry Nix.

Typically, subject cards for the PC had their subject headings typed with a red

ribbon. After bi-color ribbons became too expensive or harder to obtain, subject

heading were simply typed entirely in upper case.

Sometimes an entry was clipped from a bookseller’s catalogue and directly

imported into the OC. Other times a copy of an order slip became the Official

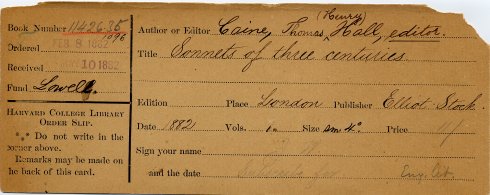

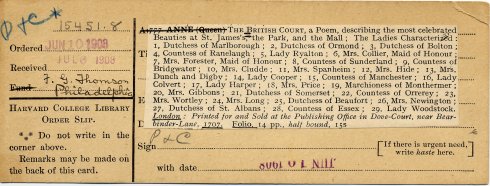

Catalogue’s entry. Included in this collection are a few order slips, each about

2.75” x 6.75”. One bears a “received” date of February 8, 1882 and the other

July 6, 1908. The latter’s bibliographic information was taken directly from a

vendor’s printed catalogue and pasted onto the order slip. Thus, informal

records migrated into the OC. Probably the intention was to generate permanent,

formal bibliographic records later, but this was never done.

To avoid fatigue and consequent errors, and as an aid to learning the catalogue,

all new professional employees and selected support staff were assigned to file

cards into the OC. Filing duty was limited to a few hours a day and would run

for several months. New filers were required to file “on the rod” so that

supervisor could first check the accuracy of filing before the rod was withdrawn

and the cards lowered into place.

The entire process was a great learning experience. It taught me to know and

appreciate that the card catalogues of great university libraries were indeed

powerful research instruments. I suspect that those that remain still are.

This site created and maintained

by

Larry T. Nix

Send comments or questions to

nix@libraryhistorybuff.org

Last updated: 06-27-09

© 2005-2009 Larry T. Nix